Table of Contents

Villagers show lithium stones discovered in Reasi district, Jammu and Kashmir.

| Photo Credit: PTI

The story so far: The Ministry of Mines in 2023 identified 30 critical minerals deemed essential for the nation’s economic development and national security. While the report highlighted India’s complete import dependency for 10 critical minerals, it did not fully address a more pressing concern — the extent and nature of dependency on China.

Is China a dominant player?

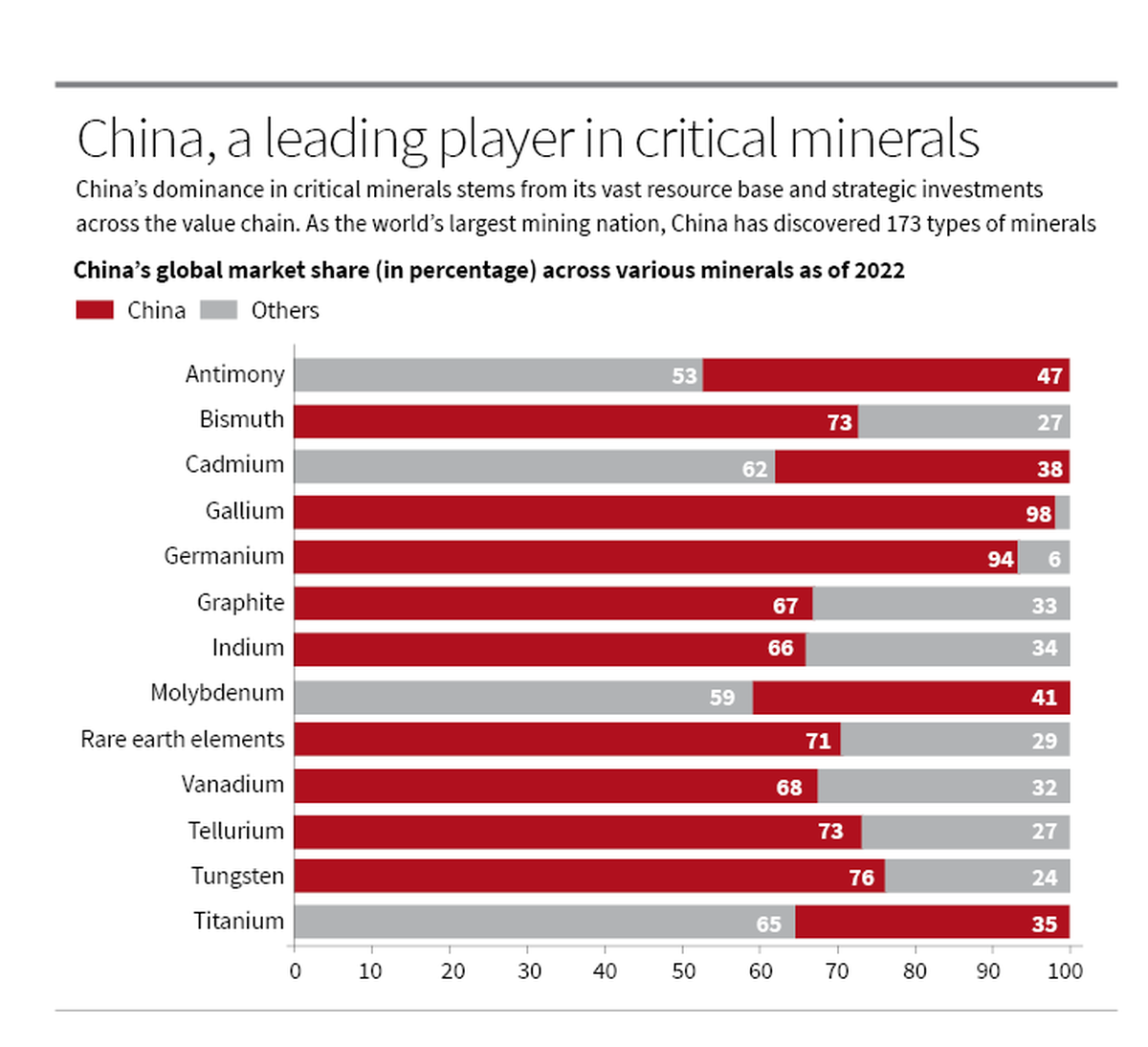

China’s unparalleled dominance in critical minerals stems from its vast resource base and strategic investments across the value chain. As the world’s largest mining nation, China has discovered 173 types of minerals, including 13 energy minerals, 59 metallic minerals, and 95 non-metallic minerals. Reserves of nearly 40% of these minerals, particularly copper, lead, zinc, nickel, cobalt, lithium, gallium, germanium, and crystalline graphite, increased significantly last year, supported by an exploration investment of $19.4 billion. This led to the discovery of 132 new mineral deposits, including 34 large ones. China’s dominance extends beyond reserves to include processing and refining, with control over 87% of rare earth processing, 58% of lithium refining, and 68% of silicon processing. Furthermore, China has strategically invested in overseas mining projects and built unparalleled midstream refining capabilities, raising supply chain vulnerabilities for countries including India, the U.S., and EU nations.

What about China’s export controls?

When it comes to China’s approach to weaponising critical mineral exports, it is strategic and calculated. Beijing primarily targets minerals deemed critical by Western nations and their allies, especially those essential for semiconductors, batteries, and high-tech manufacturing. However, China carefully balances these decisions against two constraining factors: it avoids controlling minerals which heavily depend on Western raw material imports, and it refrains from actions that could disrupt its domestic industrial enterprises or export-dependent sectors. This strategic calculus was evident in China’s 2010 rare earth embargo against Japan, its recent restrictions on antimony, gallium, and germanium exports, and its December 2023 ban on rare earth extraction and processing technologies.

Is India dependent on China?

An in-depth examination of import data of 30 critical minerals spanning 2019 to 2024 reveals India’s acute vulnerability to Chinese supplies, particularly for six critical minerals where dependency exceeds 40%: bismuth (85.6%), lithium (82%), silicon (76%), titanium (50.6%), tellurium (48.8%), and graphite (42.4%). Bismuth, primarily used in pharmaceuticals and chemicals, has few alternative sources, with China maintaining an estimated 80% of global refinery production. Lithium, crucial for EV batteries and energy storage, faces processing bottlenecks, despite alternative raw material sources, as China controls 58% of global refining. Silicon, vital for semiconductors and solar panels, requires sophisticated processing technology that few countries possess. Titanium, essential for aerospace and defence applications, has diversified sources but involves high switching costs. Tellurium, important for solar power and thermoelectric devices, is dominated by China’s 60% global production share and finally graphite, indispensable for EV batteries and steel production, faces supply constraints as China controls 67.2% of global output, including battery-grade material.

Why does India rely on imports?

Despite being endowed with significant mineral resources, India’s heavy reliance on imports stem from several structural challenges in its mining and processing ecosystem. Many critical minerals are deep-seated, requiring high-risk investments in exploration and mining technologies — a factor that has deterred private sector participation in the absence of adequate incentives and policy support. The country’s processing capabilities are also limited. This is particularly evident in the case of the recently discovered lithium deposits in Jammu and Kashmir, where despite the presence of 5.9 million tonnes of resources in clay deposits, India lacks the technological capability to extract lithium from such geological formations.

What is the way forward?

India has initiated a multi-pronged approach to reduce its dependency on China. The government has established KABIL, a joint venture of three State-owned companies, to secure overseas mineral assets. India has also joined strategic initiatives like the Minerals Security Partnership and the Critical Raw Materials Club to diversify its supply sources and strengthen partnerships. The country is also investing in research through institutions like the Geological Survey of India and the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research while promoting recycling and circular economy practices to reduce virgin mineral dependency. Production-linked incentives for extracting critical minerals through recycling also seem promising. However, transitioning away from China will require sustained investment and long-term commitment to these various initiatives.

The writer is a research analyst at The Takshashila Institution.

Published – December 24, 2024 08:30 am IST